Broadly, there are two types of experiences: my own, and all others. My own experiences originate directly within me and I recognize them as my own. All others are imaginary stories I tell myself that manifest as ideas and thoughts in my head.

Right now at this moment, I am sitting in front of my laptop in India writing this piece. This is my direct experience. However, I can imagine a friend in Italy and what he might be experiencing right now. Or what a famous tycoon or historical figure might be thinking. These are imagined.

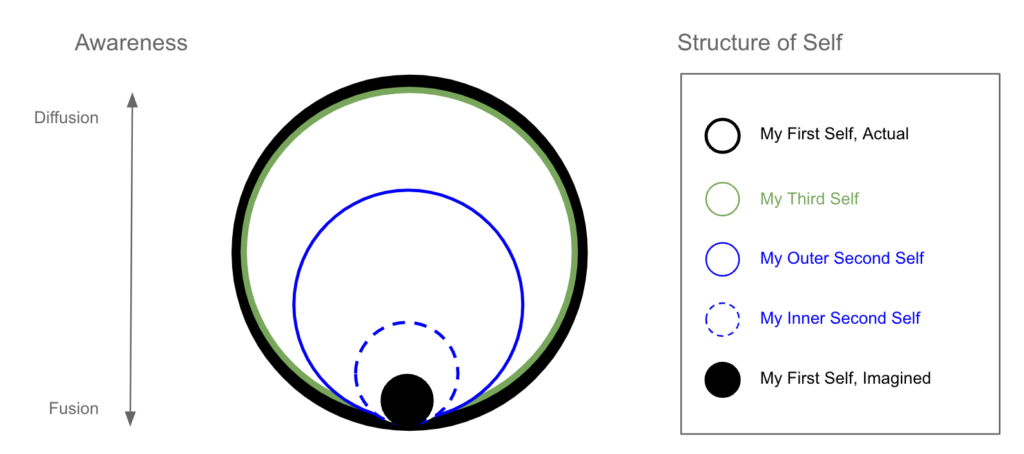

I can move in and out of these two modes: conceptual self-awareness of my own direct experience; and conceptual imagination. In the former, my inner and outer sensations center and coalesce within my head and body. In the latter, I float away into the imaginary, losing my sense of centeredness and presence.

In the Selfist Model, this is the oscillation between fusion and diffusion; between self-awareness, and imagination. In a moment of fusion, I am concentrated here, now. And in a moment of diffusion, I am diluted, dispersed, and self-unaware.

I have spent most of my life indulging my imagination. I have experienced moments of fusion, but without a basis for understanding them, I remembered them as fleeting moments of clarity and situational self-awareness. I appreciated those moments, and must have longed for more of them, but I lacked the existential framework I needed to even articulate that longing.

From an early age I was encouraged to imagine. I consumed narratives about other people, places, and times delivered in books, movies, magazines, articles, and stories. I learned about other people who built, found, explored, invented, and accomplished things in places I would never directly experience. I developed a sense of reality based on the supposed and imagined experiences of others, and accepted that my own experience was just one of countless others.

Most consequentially, I accepted the notion that truth and reality were something that must not only fit my own experience, but also account for imagined experiences of others. I was constantly looking for an equation that made sense of, not only my experience, but the experiences of others. And countless times when I thought I found something of importance, a voice in my head would conjure up a hypothetical experience I could not account for, and I would abandon my search.

Looking back, I can see that the impulse to account for other experiences thwarted all my efforts at achieving self-awareness. But now I understand the mechanism by which I lose fusional awareness, and I can readily experience fusion on demand. I know that it does not require complex meditation or discipline; it requires only understanding, and becomes easier with conviction.

In those moments of clarity when I returned to my center within, I had temporarily escaped my imagination. It felt great, but I did not know it was my own freedom I was experience. Like a prisoner who has been locked up so long he has forgotten the feeling of freedom. When he finds a way out, he looks at the beauty of a wider world outside his cell without comprehending it; before he can understand, the warden hastily pull him back into his cell where he promptly forgets the wider world right outside his cell.

My own imagination is the warden of my prison. When I leave my direct experience here and now and imagine, I shackle myself. The truth is mine to be had, and does not require me to imagine or account for the experience of others.

…