What is God? One year ago in February 2021 I wrote the following:

“God” is a construct to explain the nature of our existence. We are here, but we don’t know where or why. God is the catch-all; he’s the unknown variable that accounts for all of the missing parts in our formula.

I also wrote:

The distance between me and God is me.

I have a long history of conflict with the word “god”. Whether I have ignored or engaged it, it has stubbornly persisted in my contemplations. About 15 years ago, after my first phase of isolation and contemplations in the Himalayas, I arrived at the truth of god in a phrase: “God is the desire for peace”.

Despite the fact that I can see the truth in this one statement I first uttered a lifetime ago, it still has not settled the matter of god. But now I have a definitive answer that starts with an examination of how I have used the word throughout my life.

When I was a young boy, god was a person watching and judging me whose favor I wanted. As I grew and discovered the world, I stopped thinking about god. And by the time I was a rebellious adolescent, I openly hated religion, thinking it for dummies. Though I think I understood that God did not belong to any one religion, his loss was collateral damage.

That went on for some time after high-school. I thought Christians were stupid and the Bible was a fairy tale told to young children to brainwash them into obedient adults. But a year after high school, I began to have experiences I could not explain at the time. I would spontaneously break into tears, and began to feel that there was something much larger.

I still had not made peace with the word “god”, which I associated with religion. So that “something” turned out to be a sort of generic secular spirituality. I was a committed socialist and I did not believe there was a “god”.

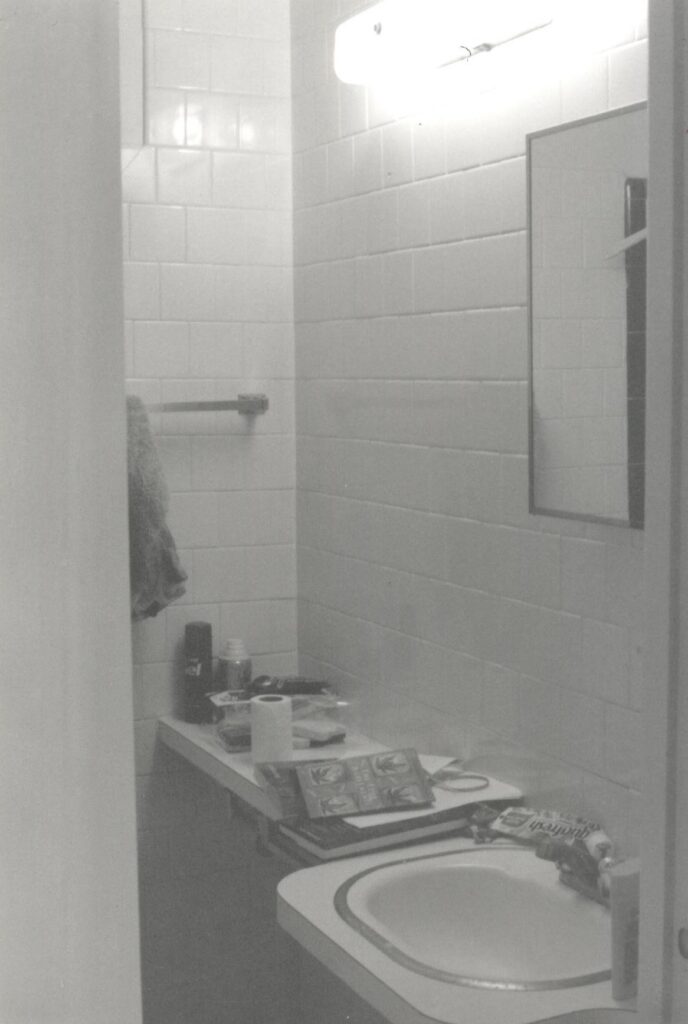

That changed a few years later when I was preparing rice and tea in my downtown Portland studio. I went to the restroom, and as I was walking in I had this sense of wellness, and the thought came to me: I should say thank you. When I did, I was instantly flooded with an indescribable, all-encompassing self-awareness. I knew everything. I was everything. In a split-moment I disavowed atheism and became a believer.

The moment was most intense for about thirty minutes. I was disconnected from my physical body, and seemed to float around the world. Coincidentally, in my Contemplative Studies class that day at PSU, the lecturer read about the epiphanies of various historical figures. I sat there in the class, half-dazed, listening to the words of St. Teresa of Avila describe exactly what had just happened to me just an hour before.

I spent hours at Powell’s looking for additional explanations of what I had experienced. I found that religious figure after religious figure wrote about the same experience as my own. I took that as a sign, and my mission was clear: I would dedicate my life to finding and living with God.

Since I could connect directly with the divine, I decided that I would not join any religion. But I felt an overwhelming pull eastward, and bought a one-way ticket to southeast Asia to live a solitary life as a monk. I stayed in Thailand for some time, then moved onward to India where I have remained to this day.

I spent my early days in the Himalayas trying to capture the ineffable. I was hoping that I would find my purpose in contemplation. It was one of the best times in my life, but without work, I could not sustain a life even in rural India. Within three years I had to return to America, where I struggled to reintegrate into society. I did, and eventually rejoined the productive workforce, ultimately spending a decade building a successful multinational IT company.

During those years, my sense of God moved deeper and deeper within. My focus became growing my business until, a decade later, it all came crashing down. I resumed my search, but this time with the means to support myself and professional, worldly experience which has turned out to be enormously helpful.

I drilled down into the language I was using, starting with “god”. How long had I accepted such a poor definition of such a vital and intrinsic feature of my existence? Looking back I could see that God was the sense of something greater and more authentic than my daily experience. But at its core, that is all God is: a belief. God is the part I believe is there, but could not always see or define. God has been the variable.

I always wanted precision, and I was dissatisfied with this amorphous definition. I wanted a definition that matched the experience I had in my early 20s that changed me from an atheist to a believer within seconds. I did not want a variable.

Without fully acknowledging it, over the past year I have used the word as a stand-in for what I have come to call my first self. And with the formalization of the triself model, I can finally state unequivocally: I do not need this word. It does not mean that the entity the word “god” represents does not play a part in my existence. To the contrary. It means that the word itself has gotten in the way of what it represents.

At its core, triselfism is the complete and absolute repossession of my existence. It is the remembrance that I created all of this myself when I woke up. The problem with the word “god” was that I could never own it, because it was a variable that belonged to everyone. In adding my own spin on it, I would always be in conflict with all the other definitions.

The triself model reveals my awakenings for what they are: an illness that hides behind distortion, strengthened by familiarity. The word “god” is a perfect example of that distortion, and as long as I need it, I cannot repossess the truth it represents.

…